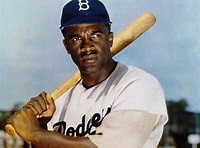

While researching my last post about Jackie Robinson’s iconic steal-of-home in game one of the 1955 World Series I made a remarkable discovery. I was studying the box score of that game reprinted on BaseballAlmanac.com and was dumfounded when I read the following baserunning notes:

SB-Robinson (1, Home off Ford/Berra). CS Martin (2, 2nd base by Newcombe/Campanella, Home by Bessent/Campanella).

Say what? Billy Martin was caught stealing home in the same game as Jackie Robinson’s iconic steal??

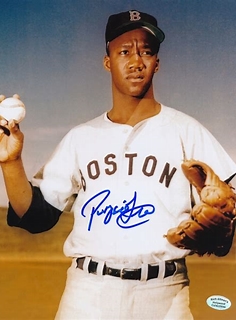

“Tis the truth!” Nobody ever talks about it, but Billy Martin tried to steal home in the same game as Robinson’s famous steal. And two innings earlier.

According to an article in SABR Martin tripled to deep left off Don Newcombe with two outs in the bottom of the sixth. Martin had already been caught stealing second earlier in the game. Joe Collins had hit a two-run homer in the inning and the Yankees had a comfortable 6-3 lead, so it was not a bad strategy to try to steal an insurance run with the bottom of the order coming up. Don Bessent had just replaced Newcombe on the mound when Martin took off for home and was tagged out by Dodger catcher Roy Campanella. The fiery pepper-pot Martin took exception to the high tag and took a few steps toward Campanella but decided instead to retreat to the Yankee dugout. He later said that he thought he was tagged in the throat. After the game Campanella spoke to the press. “Tell that little so-and-so that I missed. I tried to put the ball in his mouth.” Undoubtedly Campy knew that Billy had labeled him “spike shy” before the World Series started and so there was some bad blood between them.

It’s also quite possible that Robinson’s steal-of-home was instigated by Martin’s brazen attempt. Martin’s exceptional World Series play* had been a thorn in the Dodgers’ side for years and perhaps Robinson had had enough of Martin and needed to finally show up Bad Billy on the big stage.

Here’s a bit more psychoanalytic baseball. Remember how Yogi Berra reacted to Robinson’s steal. He basically went ballistic. Well in another World Series game one, this time in 1951 against the New York Giants, Monte Irvin, the Giant’s dynamic young outfielder slid safely past Yogi’s tag for a steal-of-home. When Robinson accomplished his feat four years later ol’ Yogi must have been thinking “not again” and went crazy.

So how rare is a straight steal-of-home in the World Series? In the 119 World Series going back to 1903 there have been only 13 attempted steals-of-home and only five were successful. The last attempt occurred in 2020 when Manuel Margot of Tampa Bay was nailed in game five against the LA dodgers.

Lonnie Smith of the Cardinals was out stealing home in game 6 of the 1982 World Series against the Brewers.

In 1955 game one Robinson was safe, and Martin was out.

Monte Irvin was safe in game one 1951.

We then have to go back 30 years for the next attempt and there were two 1921. Bob Meusel stole home for the Yankees in game two (Babe Ruth also stole two bases in that game, but not home). Mike McNally stole home for the Yankees in game one.

There were six attempts in the dead ball era and only Ty Cobb was successful when he stole home in game two of the 1909 World Series. He was out stealing home in 1908. Cobb was credited with a remarkable 32 steals-of-home in his career.

Fred Snodgrass was called out in 1911. Johnny Evers was out twice, 1907 and 1909 and Tommy Leach was nailed twice, in 1903 and 1909.

So back to Yogi’s lament as he commented on Robinson’s steal of home calling it a bad play. He may have been correct in theory. Of the 13 attempted steals-of-home in the World Series only five were successful. A .384 percentage. Good for a batting average not so good for baserunning when you consider the many other ways to score from third base even with two outs—any kind of base hit, a wild pitch, a passed ball, an error, a balk. And only once did the team with the successful steal home go on to win the World Series. That of course was the Dodgers’ by Jackie Robinson which we are still arguing about, but which may never have happened if not for Billy Martin’s brash attempt that nobody remembers.

References: Baseballalmanac.com; SABR; Matt Kelly for MLB

*Check out my Billy Martin post from 2022.